Figure 1: June 7, 1942. Page three of the Arts & Letters section of La Nación, where Borges's “Funes the Memorious", was first published.

During my research internship at CSIC, I had the opportunity to work on a project exploring the relationship between memory and deep learning under the supervision of Jesús Marco de Lucas. Our research focused on the work of Rodrigo Q. Quiroga regarding concept cells and the role of the hippocampus in memory formation and learning, as well as how this concept abstraction works in deep learning models. This topic was already fascinating, but I was immensely surprised to discover that Quiroga had written a book connecting my (current) favourit writer, Borges, and memory [1]. He relates Borges’s story “Funes the Memorious” to how memory works and its significance for learning.

I have been in love with Borges writing since my first year of undergraduate studies, so I found this connection especially interesting. Naturally, I read Quiroga’s book, and it inspired me to follow a similar path. While Quiroga’s book moves from Borges to memory, I plan to start from his insights and explore how they connect memory to deep learning research. In particular, how concepts are encoded and stored in deep learning models and their importance for learning.

Funes the Memorious

Let’s begin with a brief overview of the narrative. Nevertheless, I urge you to immerse yourself in the story directly (it spans less than 10 pages) since any summary will inevitably fall short in capturing the full depth and magnitude of Borges’s work. Additionally, I’ll be adding several direct quotes from the story, as I think there’s no better way to convey the intricacies of the discussed concepts than through Borges’ own words.

Funes the Memorious is the story of a man who, after a severe head injury, discovers an extraordinary ability, or perhaps, a curse, that grants him the capacity to remember every single detail with impeccable clarity. The argument is simple, but the real genius of Borges is that he explores the consequences of this power with his superb imagination, crafting a response that is both realistic, profound and oppressive. As we will see, Borges, without any formal knowledge of neuroscience, intuitively predicts the potential consequences of such an ability with impressive accuracy.

Borges describes Funes’ talent in the following way:

We, at one glance, can perceive three glasses on a table; Funes, all the leaves and tendrils and fruit that make up a grape vine. He knew by heart the forms of the southern clouds at dawn on the 30th of April, 1882, and could compare them in his memory with the mottled streaks on a book in Spanish binding he had only seen once and with the outlines of the foam raised by an oar in the Rio Negro the night before the Quebracho uprising.

Funes, in his bed, spends his time memorising whole encyclopaedias and remembering whole days, which takes a full day for him. Moreover, he undertakes the creation of a novel numerical system, assigning each number a unique concept that he can effortlessly recall. Yet, beyond the external consequences of this extraordinary power, Funes undergoes a profound internal transformation, altering the very mechanisms of his thought.

Not only was it difficult for him to comprehend that the generic symbol “dog” embraces so many unlike individuals of diverse size and form; it bothered him that the dog at three fourteen (seen from the side) should have the same name as the dog at three fifteen (seen from the front). His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.

As we can see, after his injury, Funes starts to have trouble generalising concepts. This difficulty extends to his sleep patterns, as Funes struggles with insomnia. Here, the paradox becomes apparent: to sleep, one must engage in the act of forgetting, a faculty that Funes no longer possesses.

Finally, Borges concludes the narrative with a brief yet profound observation on the intricacies of thought, something that eludes Funes in his new state.

With no effort, he had learned English, French, Portuguese and Latin. I suspect, however, that he was not very capable of thought. To think is to forget differences, generalize, make abstractions. In the teeming world of Funes, there were only details, almost immediate in their presence.

In short, as Borges usually does in many of his stories, he starts with a simple premise: the life of a man who can remember everything and he geniously arrives at a profound conclusion: To think, we must forget.

Solomon Shereshevskii

Figure 2: Solomon Shereshevskii

The subsequent section, now exploring neuroscience and real experiments, draws heavily from Rodrigo Quian Quiroga’s book “Borges and memory” [1], which I also highly recommend.

Solomon Shereshevskii, a journalist at a Moscow newspaper renowned for his extraordinary memory, started a remarkable research journey after a co-worker suggested he consult with psychologist Alexander Romanovich Luria. In their initial meeting, Shereshevskii astonished Luria with his prodigious memory, effortlessly reproducing sequences of up to 70 random letters or numbers. Moreover he was able to recite the sequences backwards, irrespective of whether they consisted of sounds, numbers, or words; Shereshevskii simply visualized them in his memory and could effortlessly recall them.

On another experiment, Luria asked him to recall a random mathematical formula:

\[N * \sqrt{d^2 * \frac{85}{vx}} * \sqrt[3]{\frac{267^2 * 86x}{n^2v * \pi264}}n^2b = sv\frac{1624}{32^2}\]

Not only did he repeat the formula without error, but he was able to reconstruct it 15 years later (not knowing that Luria would ask him again).

Shereshevskii’s extraordinary memory was based on a strong synaesthesia. That is, mixing the perceptions of different senses; for example, associating numbers with colours. This can be seen by reading the notes that Luria took of his conversations:

I recognise a word not only by the images it evokes, but also by a whole complex of sensations that the image triggers. It’s difficult to explain…, it’s not a question of vision or hearing, it’s a general sense I have. I usually feel the taste and the weight of a word and I don’t need to make an effort to remember it: it seems that the word appears by itself.

Finally, after Luria’s failure to measure Shereshevskii’s memory total capacity, he investigated another possibility, very aligned with Borges’s intuition: Was Shereshevskii capable of forgetting?

It resulted that forgetting was a task of Herculean proportions for him. As a consequence, Shereshevskii encountered considerable challenges in abstract thinking and reading comprehension. Despite his capacity to memorize entire pages of a book, he struggled with isolating the content to grasp its underlying meaning. Unlike the typical process where individuals extract and remember key facts to follow a narrative, Shereshevskii found himself inundated with a miriad of associations after reading just four lines.

As he describes himself below, he also had great trouble recognising voices and faces, another symptom of his inability to abstract concepts and one of the curses of his condition.

I became so interested in his voice [referring to the voice of filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein] that I couldn’t follow what he was saying…. But there are people whose voices are constantly changing. I often have trouble recognising someone’s voice on the phone, and it’s not because of a bad connection. It’s because the person is someone who changes their voice twenty or thirty times during the course of a day. People don’t notice this, but I do.

A person’s expression depends on their mood and the circumstances in which they find themselves. People’s faces are constantly changing; it is these different forms of expression that confuse me and make it so difficult to remember faces.

Following this examination, fascinating similarities emerge between Shereshevskii and Funes. Actually, it is surprising how well Borges predicted the impact that an enormous memory capacity could have on a human being, relying purely on intuition. I find particularly interesting the example of the faces, since how Shereshevskii describes it relates quite well to Funes’s inability to generalise the concept of dog, as Borges describes.

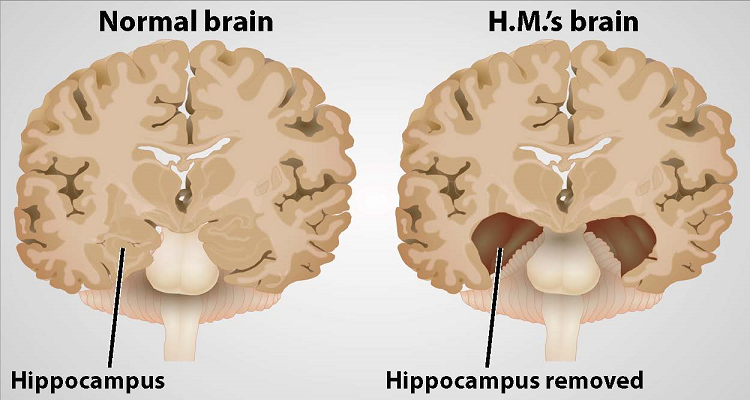

Henry Molaison

Henry Molaison (1926-2008) began experiencing epileptic seizures at age 10. His condition worsened during his teenage years, becoming resistant to even the strongest medications. By age 27, the severity of his seizures forced him to leave his job at a motor assembly plant.

At this point, neurosurgeon William Scoville proposed an experimental surgery as a last resort. Scoville had previously performed similar procedures on psychotic patients, who showed improvement after the removal of portions of their frontal lobe. With Molaison’s consent, Scoville surgically removed the hippocampus and surrounding areas from both hemispheres of his brain.

The surgery succeeded in controlling Molaison’s epileptic seizures, but it also radically changed both his life and the history of neuroscience, revolutionizing our understanding of memory.

Molaison appeared to recover normally from the surgery until a devastating side effect became apparent. He could no longer recognize the hospital staff, find his way to the bathroom, or remember daily events. In essence, Molaison had lost the ability to form new memories, a condition known as anterograde amnesia (not retrograde amnesia, which refers to the loss of memories formed before the onset of amnesia).

He couldn’t remember where things were in his house, would solve the same puzzles repeatedly without any learning, and read the same magazines over and over, never recognizing their content. Molaison lived in a constant past and a ephemeral present, which inevitably, was continuously vanishing.

However, Molaison could recall events from before his surgery. His language abilities remained intact, he could maintain conversations without difficulty and understand jokes. These capabilities require both reasoning and short-term memory, demonstrating that these cognitive functions were preserved.

When Molaison saw himself in mirrors or recent photographs, he couldn’t recognize himself, as his mental self-image remained frozen at age 27, when he had the surgery. He often described a persistent feeling of being lost. When we sleep in a hotel, we sometimes experience a brief moment of confusion, until our memory kicks in and provides the context to explain why we are there. However, Molaison lived perpetually in this state of confusion.

He described his life as constantly “waking up from a dream.” There’s a curious antithesis here with Funes the Memorious, which Borges described as a metaphor for insomnia, where all details and memories remain permanently, oppressively present.

Thanks to Molaison’s case and subsequent studies, we now understand the crucial role of the hippocampus in forming new memories. However, it’s important to note that the hippocampus doesn’t actually store memories itself. Instead, it acts as a processor, compiling experiences into memories and storaging them in other parts of the brain. This explains why Molaison could recall pre-surgery memories, they were already stored in his brain, but couldn’t form new ones. Without his hippocampus, he lacked the neural mechanism necessary to process new experiences into lasting memories for posterior storage.

Figure 3: Henry Molaison brain compared to an ordinary brain.

Hippocampus and Concept Cells

As Borges suggest, in order to think, we need to abstract concepts and relate them, we need to forget some information. This involves focusing on the essential aspects while disregarding minor details, essentially operating at a more fundamental level of understanding.

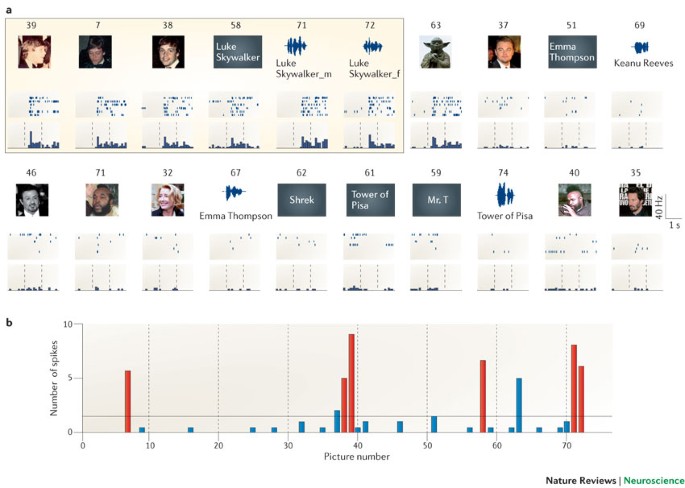

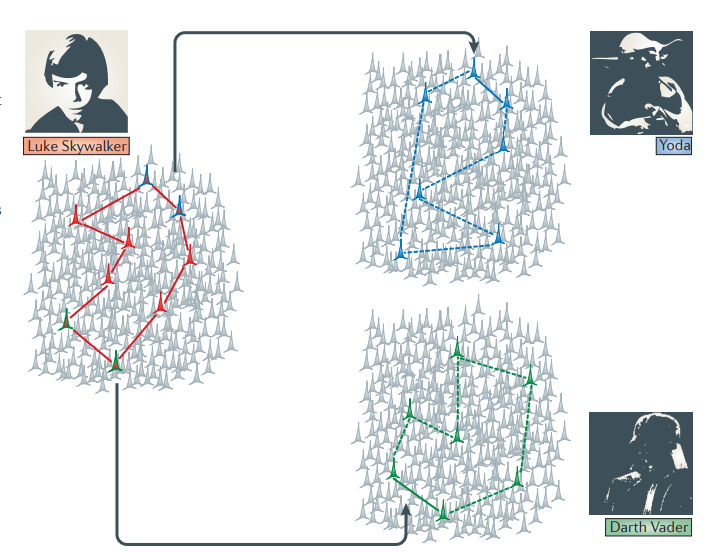

This lead us to a very intriguing and relevant discovery done by Quiroga [2]. He found that the brain contains a subset of multimodal neurons, which respond to clusters of abstract concepts centered around a common, high-level theme rather than specific visual features. This discovery originated from studies on epileptic patients, where researchers used intracranial electrodes to observe how neurons reacted to different conceptual images presented in various formats. For instance, in the image below, we see a neuron in the entorhinal cortex, the primary interface between the hippocampus and the neocortex, that fires only when the patient is presented with the concept of “Luke Skywalker”. This response occurs regardless of whether the concept is conveyed through an image, text, or audio. Interestingly, the same neuron also fires in response to the concept of Yoda.

Later, in his opinion paper Quiroga called them “concept cells” or “concept neurons” [4].

Figure 4: An specific neuron firing when the concept "Luke Skywalker" is present.

This demonstrates that the concept neurons in the hippocampus (and surrounding areas) encode representations at such a high level of abstraction that they can be triggered by different types of stimuli. Furthermore, Quiroga showed that these abstract representations can form rapidly. In one experiment, he and his team presented photos and text of themselves to patients who had only known them for two days. Remarkably, the patients already had neurons that fired in response to their photos and names.

Nevertheless, using a single neuron to encode each concept would be inefficient and would fail to capture the relationships between concepts. Instead, as Quiroga suggests in his opinion paper, overlapping representations may be key to learning associations.

Imagine a cell assembly, a group of neurons, that encodes the concept of “Luke Skywalker”. Some neurons in this assembly also respond to Yoda, while others also fire in response to Darth Vader. When the “Luke Skywalker cell assembly” is activated (for example, when seeing his picture), it can trigger associated concepts like Yoda or Darth Vader through these overlapping neural patterns. This happens because neurons that participate in multiple concept representations act as bridges, allowing pattern completion to activate related concepts.

Then, it’s not that there’s one neuron that encodes “Luke Skywalker” uniquely, but rather a specific combination of unique and overlapping neurons that creates a distinct neural signature for Luke Skywalker. This distributed representation allows for both specificity (unique identification) and associative connections (linking to related concepts). Moreover, these partially overlapping representations could form the neural basis for how we encode and learn associations and episodic memories.

Figure 5: Cell assembly for Star Wars characters

In short, the same neuron can fire for different but related concepts (like Luke Skywalker and Yoda), and there are very few of these neurons, each responding to only a few specific concepts. This is called a sparse representation, and it is also widely used in machine learning, for example in sparse autoencoders that encode information using sparse vectors [3] (vectors where most values are 0 and only a few have non-zero values).

When you see a photo of Luke Skywalker in a magazine, the initial visual recognition occurs in the inferior temporal gyrus; you don’t need the Luke Skywalker concept neuron for this. However, this concept neuron is crucial for transforming that visual perception into a memory, allowing you to later recall seeing Luke Skywalker’s photo in the magazine. These concept neurons represent the abstract concepts we use to form and store memories. Their role in memory formation makes sense because we typically remember general concepts (people, events, places) rather than exact details.

But this post is about Funes, memory and deep learning, right? So how does all this information connect to Funes?

Funes represents the extreme example of a person without the ability to abstract. Quiroga hypothesizes that without concept neurons, we would be like Funes, unable to abstract or categorize, only capable of remembering precise, uncompressed details of everything we experience, but paradoxically unable to truly think. This highlights a fundamental insight: thinking is the process of abstracting, associating concepts, and creating relationships between them. These conceptual associations then help strengthen our memories and allow us to recall them later.

Multimodal Neurons in Machine Learning

Now, we will connect this crucial idea of abstraction to deep learning. Actually, there is already a very beatiful paper that is inspired by multimodal neuros as discovered by Quiroga. The paper is called “Multimodal neurons in artificial neural networks” from OpenAI, in particular, from intepretability researches I really admire such as Chris Olah (he has a fantastic blog in which you can learn a lot about machine learning).

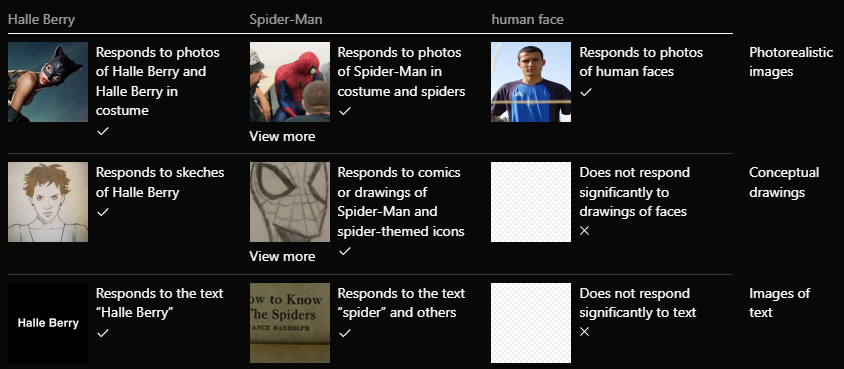

Let’s analyze it a bit. Authors discovered that individual neurons in CLIP [5] can recognize abstract concepts across different forms, from photographs to drawings to written words, suggesting that both artificial and human brains might share a fundamental approach to understanding the world by organizing information into high-level semantic concepts.

But how do they analyze CLIP’s individual neurons? They use two main approaches to understand what individual neurons are actually doing, much like Quiroga, who employs various tests to study brain function.

The first method, feature visualization, generates images by using gradient ascent optimization to find input patterns that maximally activate specific neurons. Starting with random noise, the algorithm gradually tweaks and refines the pixels until it creates an image that strongly excites the target neuron, similar to playing a game of “warmer/colder” where each adjustment is guided by how strongly the neuron responds. The resulting generated images, while often abstract, provide direct evidence of the features and patterns each neuron has learned to detect during training. I strongly recommend reading (again) Chris Olah’s brilliant post on Inceptionism. This method, along with the insights it provides into neural networks, is truly beautiful.

The second approach is more straightforward: researchers feed dataset examples through CLIP and keep track of which examples make each neuron fire most strongly. By examining these “greatest hits” for each neuron, patterns emerge.

Figure 6: Biological neurons, such as the famed Halle Berry neuron discovered by Quiroga, do not fire for visual clusters of ideas, but semantic clusters. At the highest layers of CLIP, similar semantic invariance is found.

Similar to the neurons discovered by Quiroga, researchers found that CLIP neurons in ResNet50 are “multi-faceted” [6]. This means that a single neuron might respond strongly to both photos and drawings of the same concept, or even to written words representing that concept. For instance, one neuron might activate in response to a photo of Spider-Man, a cartoon Spider-Man, or even the words “Spider” or “Spider-Man”, suggesting that it has learned to recognize the concept of “Spider-Man” across various forms of representation.

But this is not everything! The OpenAI team made another fascinating discovery about how CLIP’s multimodal neurons work together. They used a sparse linear probe, basically a regularized linear layer that maps neural activations to specific outputs while enforcing most of its weights to be zero [7]. Here the sparsity is crucial! By keeping only the strongest connections, it reveals which neurons are truly important for recognizing specific concepts while filtering out spurious correlations. Using this technique, researchers could analyze CLIP’s decision-making process when it classifies both images and text.

Then, they found that CLIP stores concepts in its neurons similarly to how Word2vec handles words (when doing text clasification): in an almost linear, straightforward way. This means these concepts follow a simple algebra that behaves similarly to a linear probe.

For example, when CLIP processes the word “surprised”, it doesn’t just register basic shock, it specifically associates surprise with positive emotions like delight or wonder. Similarly, when processing the word “intimate”, CLIP connects it with gentle smiles and romantic symbols like hearts, while explicitly excluding concepts of illness or suffering. This reveals an important limitation in CLIP’s understanding: it misses crucial nuances of human experience. For instance, its simplified view of intimacy fails to capture profound moments like caring for sick loved ones. Thus, CLIP is oversimplifying complex human experiences to prioritize clear representation of concepts within its training data.

Figure 7: Some examples of the algebraic relation between neurons

While the neuron-level analysis revealed many concepts CLIP understands, it did not tell the complete story of the model’s representation capabilities. An illustrative example is CLIP’s accurate geolocation ability, demonstrated by its creators at OpenAI. The model can identify locations with surprising precision, down to specific neighborhoods within cities. In the experiments with personal photos, CLIP consistently recognized images taken in San Francisco, sometimes even identifying specific districts like Twin Peaks.

However, this geographic knowledge isn’t stored in the way one might expect. Despite extensive searching, the team did not found any single “San Francisco neuron”, nor does the concept seem to be composed of simpler elements like “California” plus “city”. This suggests that some of CLIP’s more sophisticated knowledge is encoded in more complex ways, perhaps as vectors, directions in the embedding space, or other geometric structures we don’t yet fully understand.

This discovery actually makes sense, right? After all, neural networks have to deal with way more concepts than they have neurons, so it’s natural that some concepts won’t map cleanly to single neurons. When I was researching about concept cells in my internship, one of my main concerns was how incredibly inefficient would be for both artificial and biological systems to use a single neuron to encode just one concept. This problem could be related to one of the most fascinating concepts in Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs).

Polysemanticity and Superposition in Artificial Neural Networks

Similarly to real concept cells in the brain, the previous research demonstrated that multiple models had a single dedicated neuron encoding the concept of “Donald Trump”. This concept appeared so frequent that the ANNs consider it efficient to assign a single neuron exclusively to represent it.

To interpret ANNs effectively, it would be ideal if each individual neuron encoded a single human-interpretable concept. However, in reality, neurons can be either “monosemantic”, meaning they respond to a single feature like “Donald Trump”, or “polysemantic”, meaning they respond to many unrelated features [8,9].

Figure 8: Polysemantic neuron which responds to cat faces, fronts of cars, and cat legs

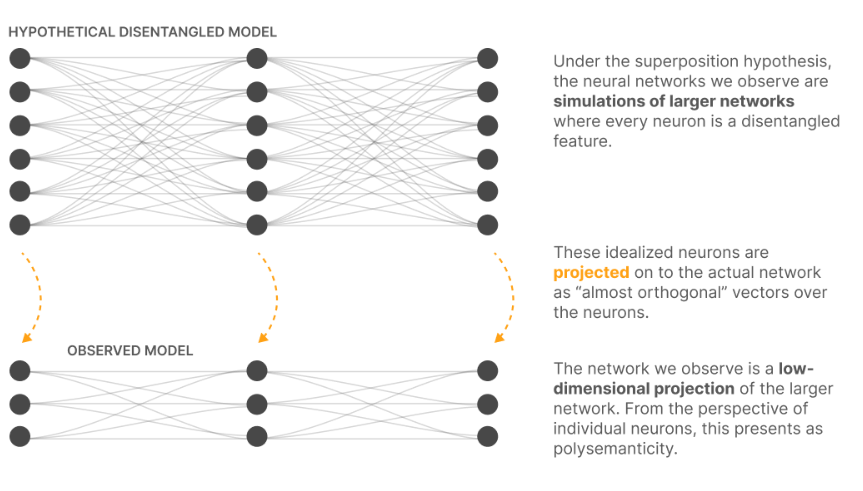

The reasons behind this phenomenon are not yet fully understood, but several hypotheses attempt to explain it. One of the most interesting is the Superposition hypothesis, proposed by well-known interpretability researchers at Anthropic [10].

(Now, I will use concept and feature interchangeably to maintain consistency with the earlier narrative. However, it’s important to note that concepts are typically human-interpretable, while features are properties of the input that a sufficiently large neural network reliably assigns a neuron to represent. In contrast to concepts, features don’t need to be human-interpretable. They simply need to be elements of the input data.)

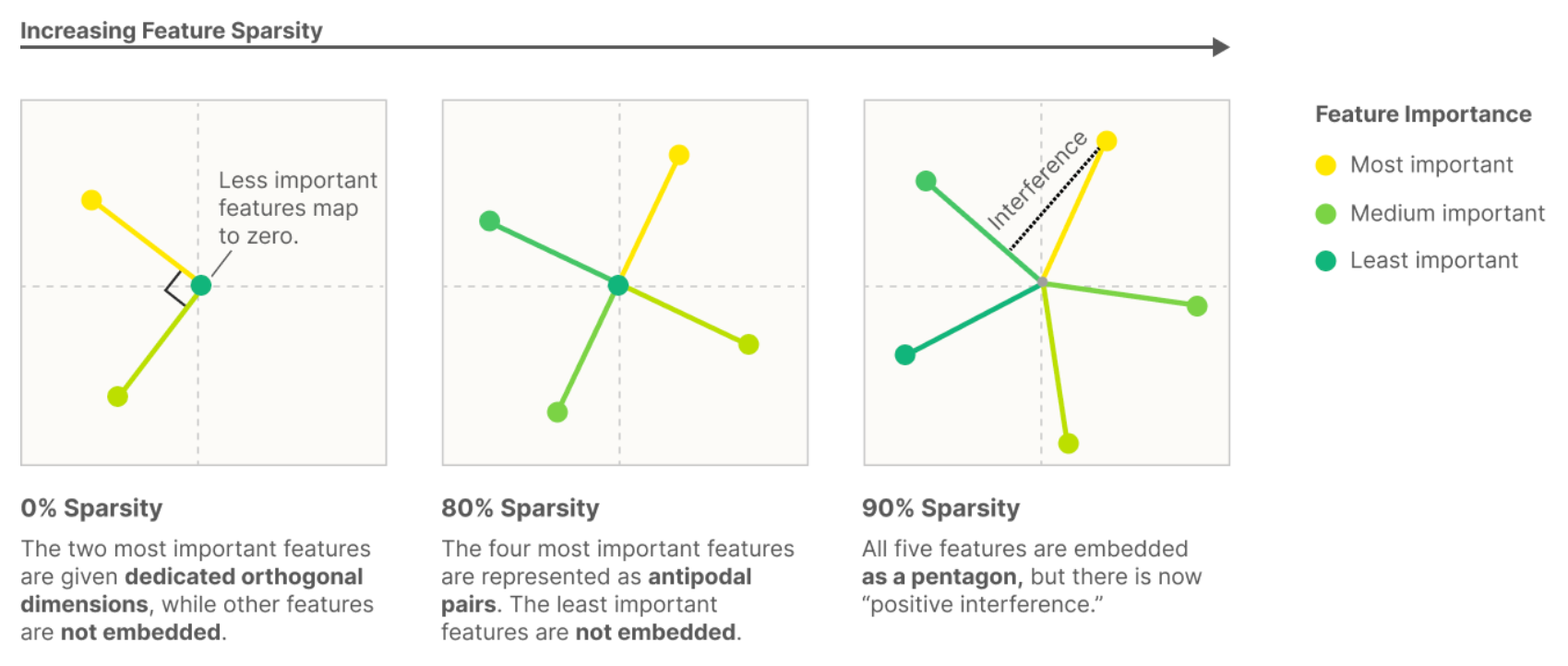

They use toy models, small ReLU networks trained on synthetic data with sparse input features, to investigate how and when models exhibit superposition. That is, when they represent more features than they have dimensions.

Consider a simplified model that takes five features of different importance levels and embeds them into a two-dimensional space, using a ReLU activation function, while varying feature sparsity. In the dense case (where features have meaningful values most of the time), the model behaves similarly to Principal Component Analysis, learning to represent only the two most significant features as an orthogonal basis while discarding the remaining three.

However, when feature sparsity is introduced (features are frequently zero or inactive), the model demonstrates superposition: it can encode additional features by allowing controlled interference between them, and more surprisingly, can perform computational operations while maintaining this superposed state.

Figure 9: As sparsity increases, the model fits more features than it has dimensions.

This observation leads to a super interesting interpretation of neural network behavior: the networks we train in practice may be effectively operating as compressed simulations of much larger, highly sparse networks. That is, our trained models might be implementing the same computational patterns and representing the same features as a hypothetical larger network would, but in a more compact form where multiple features and operations coexist in the same dimensional space through controlled interference patterns.

Figure 10: ANNs could be simulating bigger and more sparse ANNs.

But why is this happening?

As we have seen before, the key lies in a fundamental truth about our world: sparsity. Think about looking at a photo: at any given spot, you’re unlikely to find a dog’s head, a horizontal line, or a perfect curve. In human language, most words aren’t about Martin Luther King or about Science Fiction literature. This sparsity principle, combined with two crucial mathematical foundations, enables neural networks to achieve efficient information encoding.

The first mathematical fact is the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma, which demonstrates that while an n-dimensional space can only contain n truly orthogonal vectors, it can fit exp(n) “almost orthogonal” vectors. The second is compressed sensing [11], which shows that sparse vectors can be accurately reconstructed even after projection into lower-dimensional spaces, something impossible with dense vectors.

Neural networks exploit these properties by representing concepts as almost-orthogonal directions in the vector space of neuron outputs. Since the features are only almost-orthogonal, one feature activating looks like other features slightly activating. Tolerating this “noise” or “interference” comes at a cost. But for neural networks with highly sparse features, this cost may be outweighed by the benefit of being able to represent more features. The network further mitigates this cost through the non-linear activation functions that filter out low-level noise. This elegant trade-off allows neural networks to represent exponentially more features than their dimensional space would traditionally allow, with the sparse nature of concepts ensuring the benefits substantially outweigh the interference costs.

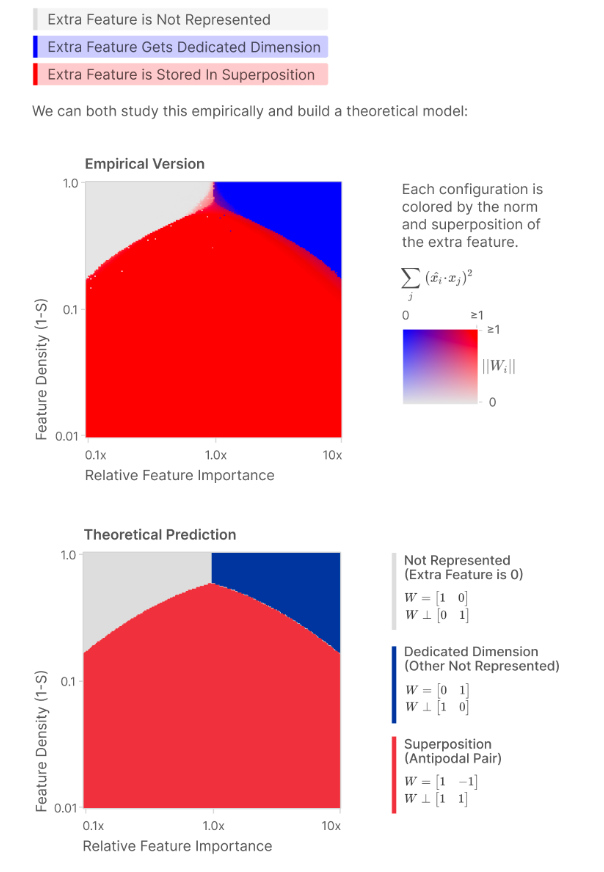

One of the most fascinating aspects of superposition is how it emerges during neural network training through distinct phase transitions. When training a model, each feature can reach one of three possible states: (1) it may remain unlearned, (2) become encoded in superposition with other features, or (3) acquire its own dedicated dimension in the representation space. These transitions don’t occur gradually but rather exhibit sharp, discontinuous changes characteristic of phase transitions in physical systems.

The conditions ruling these transitions depend on a complex interplay between feature sparsity and relative importance. While sparsity is a prerequisite for superposition, the relationship isn’t linear, it interacts with feature importance in determining the final representational state. This phase-change behavior appears in both empirical observations and theoretical models, where the optimal weight configurations show abrupt, discontinuous shifts in both magnitude and degree of superposition.

Figure 11: Phase change in ANN training.

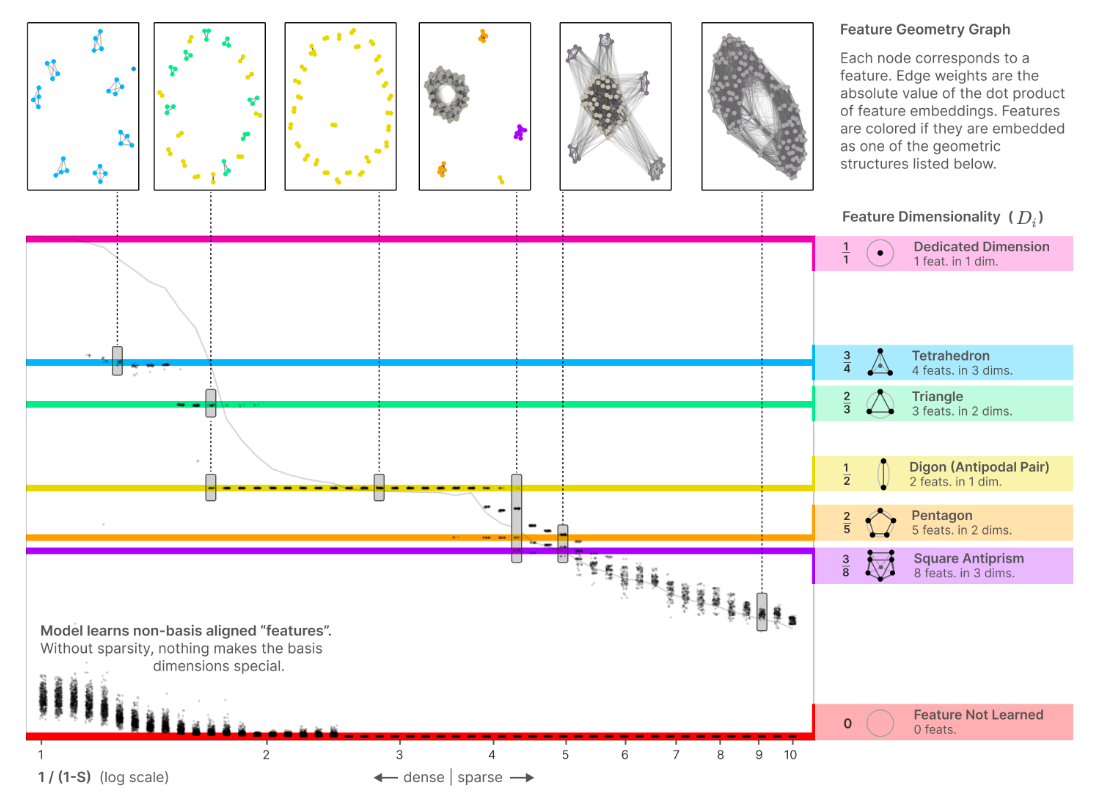

But this is not everything! After deeper exploration, features seem to organize themselves into geometric structures such as pentagons and tetrahedrons!

When neural networks learn to represent features, they don’t always give each feature its own complete dimension. Instead, features can share space in fascinating ways, occupying what they call “fractional dimensions”. I don’t want to make this post mathematically heavy, so instead of copying the formula I will try to describe its meaning.

The dimensionality measure tells us two crucial things about how a feature is represented in the network: How strongly it’s encoded versus how much it has to share its space with other features. If a feature has a strong presence in the dimension but doesn’t share space with many other features, it gets a higher dimensionality score. Conversely, if it’s strongly represented but heavily overlaps with many other features, its effective dimensionality will be lower because it’s sharing its space. Then, this ratio gives us a measure of how much of a dimension each feature truly “owns” in the network’s representation space.

What’s fascinating is that these fractional dimensions aren’t random. Features tend to organize themselves into specific, stable patterns where they share space in precise ways. For example, when two features pair up perfectly, each gets exactly half a dimension (Dimensionality=1/2). What’s even more interesting is that when we add up all these fractional dimensions across features, they typically sum to the total number of dimensions available. The network is trying its best to efficiently use the available space.

This discovery reveals that superposition isn’t just one thing. It’s actually a collection of distinct states, each with its own geometric pattern of how features share space. As the authors explain, it’s similar to how ice isn’t just “frozen water” but can form different crystal structures depending on conditions. In a somewhat similar way, neural network features appear to exhibit multiple phases within the broader concept of “superposition”.

Figure 12: The geometry of superposition.

Finally, to close the circle, we can relate the Superposition hypothesis to biological neurons. A key contribution of this work is introducing feature co-occurrence probability as a central concept in neural encoding. This idea reveals that maximally-dense distributed codes work best when items never need to be represented simultaneously, allowing for extreme superposition. For instance, in a motor task where a person reaches for spatially separated targets, only one target needs to be encoded at a time. However, when features must be represented together, like visual neurons encoding white noise (which contains all spatial frequencies), a code with less or no superposition works better to avoid interference. These insights agree with existing neuroscience hypotheses [12] about how the brain might use highly compressed representations for long-range communication between areas while maintaining sparser representations for local computation.

The paper is quite extensive but incredibly fascinating. If you’re interested, you can read it here. Also, kudos to the authors for the excellent images throughout!

Note - 20/11/2024: Chris Olah, the lead researcher behind this investigation, has participated in a wonderful podcast with Lex Fridman, where he discusses the superposition hypothesis and the interpretability of artificial neural networks in general. Highly recommended!

Conclusion

In this blog, we explored the connection between the fictional character Funes the Memorious, concept encoding in biological neural networks, and how concepts might be represented in ANNs. For ANNs, the key to concept encoding lies in the sparsity of concepts in reality. Through gradient descent, these networks exploit this sparsity by assigning neurons to represent multiple concepts, learning to manage the resulting interferences, and thereby increasing the network’s information storage efficiency.

This suggests a beautiful new perspective on Artificial Neural Networks: they might be a projection or simulation of a larger, more sparse network.

Additionally, the fact that certain concepts consistently get a dedicated neuron in each model, based on their frequency in the data, similar to how our does, it’s a fascinating insight. It suggests that both ANNs using gradient descent and biological networks converge on the same optimal way of representing information. This hints at the existence of a natural, universal optimal way for encoding information in networks, regardless of whether they are artificial or biological. Of course, more research is needed, but this is incredibly exciting!

That’s all for today. Keep learning, and keep forgetting! Don’t be like Funes!

References

[1] Quiroga, R. Q. (2012). Borges and memory: Encounters with the human brain. Mit Press.

[2] Quiroga, R. Q., Reddy, L., Kreiman, G., Koch, C., & Fried, I. (2005). Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain. Nature, 435(7045), 1102–1107.

[3] Ng, A. (2011). Sparse autoencoder. CS294A Lecture notes, 72(2011), 1-19.

[4] Quiroga, R. Q. (2012). Concept cells: the building blocks of declarative memory functions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(8), 587–597.

[5] Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., … & Sutskever, I. (2021, July). Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 8748-8763). PMLR.

[6] Nguyen, A., Yosinski, J., & Clune, J. (2016). Multifaceted feature visualization: Uncovering the different types of features learned by each neuron in deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03616.

[7] Radford, A., Jozefowicz, R., & Sutskever, I. (2017). Learning to generate reviews and discovering sentiment. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.01444.

[8] Olah, C., Cammarata, N., Schubert, L., Goh, G., Petrov, M., & Carter, S. (2020). Zoom in: An introduction to circuits. Distill, 5(3), e00024-001.

[9] Olah, C., Mordvintsev, A., & Schubert, L. (2017). Feature visualization. Distill, 2(11), e7.

[10] Elhage, N., Hume, T., Olsson, C., Schiefer, N., Henighan, T., Kravec, S., … & Olah, C. (2022). Toy models of superposition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.10652.

[11] Donoho, D. L. (2006). Compressed sensing. IEEE Transactions on information theory, 52(4), 1289-1306.

[12] Ganguli, S., & Sompolinsky, H. (2012). Compressed sensing, sparsity, and dimensionality in neuronal information processing and data analysis. Annual review of neuroscience, 35(1), 485-508.