“Art is a mechanism constantly trying to destroy itself, always questioning what is or isn’t art.”

Those were the words my uncle, the artist Pipo Hernandez, shared with me over dinner at his house while we discussed whether AI could truly be an artist. (If you’re curious about his work, you can check it out here, I absolutely love it!)

A few months later, I found myself defending my Master’s thesis, “Alien Recombination: Exploring Concept Blends Beyond Human Cognitive Availability” at the Technical University of Munich. I had the privilege to conduct this research alongside a brilliant team from both the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

Our project explored ways to improve artificial creativity, an admittedly ambitious goal for a master’s thesis. To be honest, we couldn’t hope to fully address such a complex challenge, especially since we’re still discovering new dimensions of the problem itself.

In this post, I want to share my thoughts about the nature of creativity, interesting theories I have read and the challenges of implementing it in machines, along with potential paths forward. Moreover, we will focus more in Art, the human pinnacle of creativity.

This isn’t meant to be a scientific article, think of it more as an invitation to dialogue, a way to organize my thoughts and hopefully inspire others to become as passionate about this topic as I am.

Types of Creativity

Creativity is one of those concepts that seems to slip through our fingers just when we think we’ve grasped it. Some view it as a process that emerges from imagination [1], where imagination is seen as a reconstructive process based on prior knowledge [2]. Others define it as the process by which an individual generates new ideas or patterns using the symbols of a given domain [3]. Additionally, some interpretations view creativity as a fully combinatorial process, involving the combination of existing representations [4][5].

In computer science, Margaret Boden’s definition has been particularly influential [6]. She describes creativity as “the ability to come up with ideas or artifacts that are new, surprising, and valuable” [7]. What makes this definition so useful is how it breaks creativity into “measurable” components: value (high quality and social acceptance), novelty (significant difference from existing artifacts), and surprise (deviation from expectations).

Boden identifies three distinct types of creativity:

Combinatorial creativity, that involves creating unexpected combinations of familiar ideas, like pairing chocolate with chili in a recipe.

Exploratory creativity, finding new solutions within established frameworks, like a jazz musician discovering fresh melodies while working within traditional chord progressions.

Transformational creativity, that involves fundamentally changing how we think about something. Think of Einstein’s theory of relativity revolutionizing our understanding of space and time, or how Picasso’s cubist paintings transformed 20th-century artistic expression.

Don’t underestimate the power of Combinatorial Creativity

Combinatorial creativity is often considered the most basic form of creativity. While some studies suggest that LLMs are primarily limited to this type of creativity, lacking the deeper exploratory or transformative capabilities found in other forms [8], we shouldn’t undervalue the power of combining different concepts.

In fact, the combination of concepts is a phenomenally powerful mechanism for creating wonderful things. Most of the creative works we love are, to a large degree, combinations of concepts we already know. Think about Star Wars for example. George Lucas created it by mixing westerns, samurai stories, feudal societies, and Flash Gordon, among other influences. Or consider Rapture, the charismatic city from Bioshock, it’s basically a combination of a submarine city, art deco architecture, Ayn Rand’s ultra-liberal capitalism, and a drug crisis. Usually, most of world building is done by composition.

The truth is, it’s incredibly difficult (for me, it feels impossible, but I wouldn’t presume to generalize this limitation to brighter minds than my own) to create something entirely new without any grounding in prior knowledge. Try imagining something you’ve never seen before that has absolutely no resemblance to anything in the observable universe. Even H.P. Lovecraft, when attempting to describe his “unspeakable” cosmic gods, had to rely on familiar terms like tentacles and anthropomorphic features, or describe recognizable sensations to convey what Cthulhu and other entities might look like.

So while combination, when thoughtfully applied, can be an incredibly powerful creative strategy, I think there’s still a vast unexplored space of possible combinations out there, waiting to be discovered.

In my Master’s thesis, we explored this idea in the visual art domain. We hypothesized that there exists a huge, unexplored space of concept combinations, not because these concepts are incompatible, but because of the natural limitations of an individual artist’s cultural horizon, including their geographical, temporal, and social context.

Let me give you an example: the concept of an “airplane” simply didn’t exist during the Renaissance period, making it cognitively unavailable to artists of that era. And even today, when we’re familiar with both concepts, there’s still this subtle bias against combining Renaissance style with airplanes (even if it could be a very cool idea). This relates to what cognitive scientists call availability bias - we heavily rely on immediate examples that come to mind when thinking about a topic, which can limit our exploration of novel ideas.

Although trained across temporal and cultural boundaries, generative AI models inevitably absorb human biases. As a result, these models can expect to predominantly produce cultural artifacts that align with human cognitive availability. James Evans and his team showed that counteracting such a bias could be key to algorithmic augmented scientific discovery [7, 8].

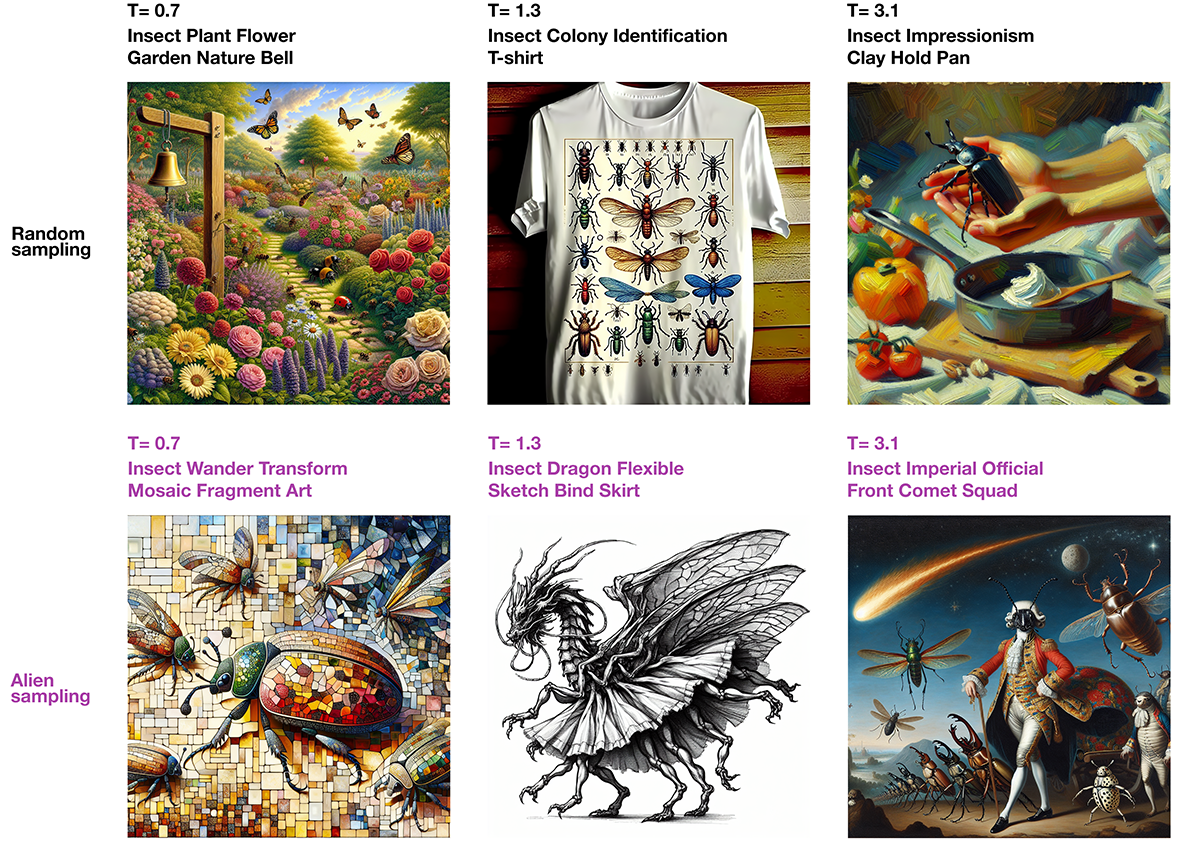

We developed a system that generates novel visual art concept combinations by modeling and counteracting these cognitive biases. We worked with the set of concepts extracted from the artworks of WikiArt, and two probability distributions using fine-tuned LLM models. The first is what we call the Artwork-level distribution, P(a|S), which captures the probability of finding concept A in an artwork that contains a set of concepts S. The second is the Artist-level distribution, Q(a|S), representing the probability of an artist using concept A given they’ve used concepts S in their whole artistic work.

The key difference between these distributions is their scope. If an artist has used concept A in one artwork and concept B in another, both concepts are within their cognitive reach, even if they’ve never combined them in a single piece. Our method looks for what we playfully call “alien” combinations (inspired by James Evans’ work on alien scientific discoveries) by finding combinations that are surprisingly improbable in the artist-level distribution using a ranking system.

This leads us to discover combinations that are hard to find or conceive naturally because they contain concepts that are unavailable to all artists that have used a given set of concepts. For instance, no artist who worked in the Renaissance style could have known about airplanes. If they did, that would mean these concepts had coexisted in time or imagination (or that Renaissance style has returned in mainstream art, that has not happened as far as I know.)

Of course, we’re making some assumptions here, like limiting our concept world to those used in WikiArt artworks, and assuming artists express all their conceptual knowledge in their work (which might not be realistic, an artist might know about something but choose never to paint it). But it gives us a interesting approximation of cognitive availability and lets us explore these low density or empty spaces of artistic combinations that have never been attempted and hard to even conceive of in our world (dataset).

If you’re interested, you can read the paper here However, this post aims to address a broader perspective beyond just discussing the paper. The key point is that while combinatorial creativity is often considered the least interesting and is frequently dismissed as the simplest form, it still holds immense power and unexplored potential especially with AI systems now capable of finding and exploiting what we have overlooked. Our paper is merely a small step, a toy idea, compared to the progress that still lies ahead.

Figure 3: A dragon insect with a skirt or an insect army commanded by an imperial official, combinations absent in our training dataset, but also cognitively unavailable to all artists on the domain.

Creativity is Divergent

Figure 4: Ultraleve, Pipo Hernandez

Now, let’s dive into the tricky part: how creativity may work in practice, what is its essence.

This led to an interesting conversation with my uncle about making an AI artist. I suggested that understanding creativity in computational terms, or at least having a nuanced definition that can be approximated by a program, could help to achieve this, if possible. Therefore, I asked him to recall how he came up with the idea for his latest artwork, which was exhibited at ARCO, Spain’s International Contemporary Art Fair.

Explaining this artistic piece goes against its essence, but trust me, we could discuss its intricacies for hours. Still, I’ll try to focus on the main point. As you can see in Figure 4, the piece consists of a wall displaying Romanticism paintings with black weighing scales on the floor. The mere presence of Romantic paintings in a Contemporary Art fair is already surprising, but the piece explores current dialogue mechanism between artwork and spectator.

In our current era, when confronted with art we don’t immediately understand, we often demand quick explanations. We’ve lost our patience for mystery, for engaging in slow but intense dialogue with an artwork, for dealing with ambiguity. Conditioned by fast internet and instant information, we expect immediate answers from art. However, art often transmits questions rather than answers, usually philosophical questions without clear solutions.

The piece juxtaposes two elements: Romantic paintings, which invite philosophical dialogue and embrace mystery (a highlight of Romanticism), and weighing scales, which represent our modern preference for functional questions with immediate, concrete answers. Functional questions are asked to obtain factual information. When you step on a weighing scale, you are essentially asking, “What is my weight?” and you quickly receive an answer. At the fair, observers would quickly tire of contemplating the paintings and start playing with the scales instead. The whole scene captures our discomfort with ambiguity, our intolerance to questions that might not have definitive answers, our fear to the abyss. It shows how quickly we retreat to the safety of measurable, quantifiable responses in a world we struggle to understand, avoiding questions that lack factual, immutable answers.

Art is not meant to deliver easy truths; it is a dialogue, a philosophical conversation that often raises more questions than it answers. Moreover, this dialogue shifts over time, even if the artwork remains unchanged, because it is influenced by the current cultural context. Borges’ story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” is a brilliant exploration of this idea. It’s a must-read if you haven’t encountered it yet! But now, let’s return to the creative process.

As I mentioned, when I asked my uncle about the origins of his artwork, he told me that it started with a problem: “There is no true 21st-century art, everything we’re seeing is just an extension of 20th-century movements. Like the period before Romanticism emerged, we’re in a creative crisis, living in the shadow of the previous era’s huge influence, without a distinctive artistic style to call our own.”

That’s where it began, with framing the problem. And then came the real magic, that thing that machines will find so hard to replicate. As he put it: “So I thought… if we’re still showing 20th-century art in 21st-century exhibitions, why not go even further back? What about bringing Romanticism into the present?”

This was the seed, the initial spark that started the posterior creative process. Like a butterfly effect in motion, this simple idea underwent a series of transformations and mutations, eventually evolving into the final piece that captured both the irony and the deeper truth about our relationship with art today.

The brilliance of this approach shows exactly why machines struggle with creativity. While current AI can analyze patterns and mix pixels or words in statistically likely ways, it can’t truly venture into out-of-distribution spaces without failing. My uncle’s creative leap wasn’t just about combining different time periods, it came from asking an unlikely question about his environment and current knowledge, then trying to answer.

AI models excel at generating good responses, but they lack the ability to ask good questions that serve as stepping stones to greater insights. Divergent thinking doesn’t arise from gradient descent, which is designed to follow the steepest path to minimize a loss function. Instead, it is driven by curiosity, intentionally exploring unknown areas looking for something interesting. Where AI models see noise, human curiosity might find opportunity, a chance to discover novel and unexplored solutions rather than just optimize within known boundaries.

Searching for Compression

However, we are computer scientists. We may have identified the essence of the creative process, asking interesting questions through a divergent process, but how can we translate this into a computational framework?

I find particularly interesting Varshney work on defining creativity in a mathematical way [9]. His framework establishes creativity as a formal optimization problem that balances novelty and quality in a combinatorial space. He shows that the fundamental tradeoff in creativity is similar to Shannon’s capacity-cost function from communication theory, a connection we will explore further. While his research suggest that communicative intent may constrain both quality and novelty of creative artifacts due to information rate limitations, I believe the framework has an essential limitation: it takes a static global view of creativity. This is evident in how it treats quality as a fixed measure and assumes that novelty of the artifact should be measured against all the remaining artifacts in the domain. Then, the framework is overlooking the role of subjective observers, whose perspectives determine whether an artifact is perceived as novel or interesting, allowing for different creativity evaluations for the same artifact.

Now, let me introduce a curious concept [10] from Jürgen Schmidhuber that might sound crazy at first, but ended up feeling incredibly intuitive to me: creativity is fundamentally about finding data compressions.

Figure 5: Convergence, Jackson Pollock

We live in an environment full of historical data: our entire record of actions, observations, experiences and reward signals. Simple explanations of the past often reflect some repetitive patterns, which are useful for predicting the future. Therefore, any intelligent system aiming to achieve future goals should be driven to compress its sensory history. To achieve this, we identify regularities and create compact internal representations or symbols for frequently recurring elements. Even when predictions aren’t perfect, we can still compress data effectively by using shorter codes for events that occur with very high probability. For example, since the sun rises every day, it’s efficient to create a symbol like “daylight” to represent this recurring event, rather than continuously storing raw sensory data about each sunrise.

In principle, any regularity in our data history can serve as a basis for compression. This compressed version of the data acts as a simplified explanation of our experiences, enabling us to process and predict the world more effectively.

Interestingly we can define beauty and interestingness in this context. Given a subjective observer O, we can identify the subjective beauty of an artifact D for O as being proportional to the number of bits required to encode D, given the observer’s limited prior knowledge. For example, to efficiently encode previously seen human faces, we might create an internal representation of a “prototype” face. When encoding a new face, the system only needs to record the deviations from this prototype, significantly reducing the amount of information required. Therefore, something appears beautiful when it fits easily into our current representation, like a face that closely matches our mental “prototype”, or a mathematical proof that can be expressed simply. This is why we often find symmetrical or proportional things beautiful, and why we tend to find faces beautiful when they remind us of faces we see often, including our own.

However, what is beautiful is not always interesting. A beautiful object is interesting only as long as it remains novel, while the observer is still learning to compress the data effectively by identifying the algorithmic regularities that make it simple. Once these regularities are fully encoded and the compression is optimized, the novelty vanishes, and the observer’s interest diminishes.

Then, interestingness can be understood as the derivative of beauty. As the observer improves their compression algorithm, data that initially seemed random becomes more regular and easier to encode, requiring fewer bits. The data remains interesting and rewarding as long as the process of improving compression continues.

As a result, curiosity can be defined as the search for interestingness, the drive to explore on experiences that are currently incompressible but are expected to become compressible with further learning, maximizing the potential for future understanding and compression progress. It involves actively seeking novelty and avoiding both fully predictable (boring) and seemingly irreducible (unlearnable) phenomena. I like to think of this as a movie. If you could predict all the subsequent frames just by looking at one, the movie would be predictable and boring. However, if each frame were completely unpredictable based on the previous one, the movie would become chaotic and unlearnable.

But how does creativity fit into this perspective of compression? Intuitively, creativity is the ability to find novel, meaningful and effective ways of compressing data, discovering overlooked regularities in our historical information. Thus, science and art are surprisingly similar, they’re just approaching this compression differently.

Science has historically proceeded incrementally, analyzing just a small aspect of the world at any given time, trying to find simple laws that allow for describing their limited

observations better than the best previously known law, essentially trying to find a program that compresses the observed data better than the best previously known program. For example, take Newton’s discovery of gravity. This was essentially a way of compressing a regular pattern in the data: things fall. With this insight, if we want to store the event of a lemon falling from a tree, we don’t need to save every single bit of every frame of it dropping. As soon as the lemon detaches from the tree, we can predict its entire trajectory based on the concept of gravity, saving a lot of space.

Now look at Einstein’s theory of relativity. It’s a very novel and efficient data compression. Sure, the theory is complicated, but at its core, it boils down to: The laws of physics are the same for all observers in inertial frames, and the speed of light in a vacuum is constant regardless of motion. When this is assumed to be true, the rest of the theory and their implications unfold naturally, aligning with empirical observations. This means we no longer need to store certain bits of historical data explicitly, as they can be derived from the theory. Einstein essentially uncovered a new and very efficient way to compress the data of our universe, allowing us to predict real-world phenomena with precision, reducing the informational “storage cost” of our environment.

Art, in contrast, is a more elusive domain. Extending this idea of compression to art, we can see parallels but also key differences. Science focuses on formally identifying and defining a compression rule by discovering new regularities in the data, essentially creating efficient, predictive models of reality. Art, on the other hand, is about presenting information in a uniquely compressed way, with an emphasis on novelty than strict prediction accuracy.

My uncle didn’t just recite a message, he compressed complex ideas about our relationship with Art combining paintings and weighting scales. As an artist, his role was to carefully select and compress intricate meanings into a few bits (pixels on a painting, words in a poem, or the scenario of paintings and weighting scales). Our role as subjective observers is to decompress this information, extracting meaning from it.

However, Art is inherently subjective, and this subjectivity is perhaps its most defining characteristic. What is subjectivity if we are treating art as compressed information? Subjectivity arises from the differences in the historical data and knowledge representation between the artist and the observer.

When an artist creates, they rely on the shared experiences and historical data of living in the same world as their audience. They identify patterns in emotional and experiential domains to craft an artifact that has high probability to resonate with the observer’s own historical data. Even when artists don’t consciously consider an audience, their work often still succeeds because artists and observers inevitably share some subset of historical data and the regularities within it.

Then, when we understand an artwork, we’ve discovered shared regularities in our collective experience. Even when we interpret things differently or have different backgrounds, we’re drawing from fundamentally similar human experiences, similar historical data. That is why Art works, and discovering these connections can evoke powerful emotional responses like crying, laughing, joy, or terror.

The flip side is that if the observer is missing some part of the historical data or representations, they might not decompress the information exactly as the artist originally did. However, as I mentioned earlier, while this could be a problem in science, it’s not an issue in art. Art encodes information in a way that allows observers to uncover other regularities, leading to decompressions that are meaningful personal interpretations.

For example, I might not fully understand Romanticism history and thus cannot grasp my uncle’s intended full message in the artwork. Yet, I might interpret the weighing scales in his artwork as black mirrors reflecting my act of artwork observation, extracting a unique message about my own subjective experience. This is why art has no dead ends, it has no fixed rules. Unlike science, the decompression process in Art can lead to entirely different and equally valid results.

Again, Borges’ Pierre Menard captures this concept beautifully. Even an identical text can produce entirely different interpretations depending on the observer’s individual history and associations.

Thoughts on Art as Compression

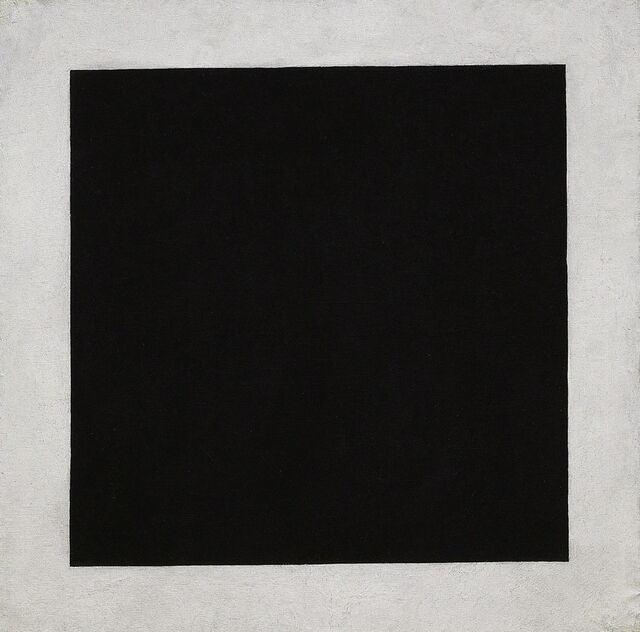

Figure 6: Black Square, Kazimir Malevich

As much as I enjoy computationally-focused philosophical theories, and as much as I admire the beauty (or perhaps the amount of compressed bits) of Schmidhuber’s framework, I was born into a family of artists and have been surrounded by art creation my entire life. I exist in two worlds: my computer scientist side is fascinated by the idea of creativity being fully computational and replicable by machines, and I am passionate about advancing this research. Yet, another part of me wants to believe there is still something deeper to discover—that creativity cannot be reduced to something so straightforward.

Sometimes, I see both perspectives as equally beautiful. On one hand, there is the promise of a future where AIs create art and share information in innovative ways that we can admire. On the other, I fear that the intimate human connection, our ability to communicate our fears, joys, and sorrows through art, might be lost, overshadowed by the relentless speed and abundance of AI-generated creations.

Now, let’s explore what might be missing from this perspective.

In computer science, we are increasingly used to explaining the universe in terms of computation and information transmission. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy this kind of thinking, it’s very elegant and rewarding. However, we must recognize that a recurring pattern throughout Western intellectual history is the tendency to interpret the universe and the human mind using the most advanced technological paradigm of the time [12]. For example, in ancient Greece, the mind was compared to a hydraulic clock; during the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries, it was likened to a clockwork mechanism. With the industrial revolution, the metaphor shifted to steam engines, and since the 1930s, the dominant analogy has been the human mind as a computer.

As subjective observers having historical data and context, we try to understand the world in the most advanced terms we can. However, we need to be careful about information we might be losing by constraining the empirical data in our information theories.

I find Jürgen Schmidhuber’s theory very elegant. It works well for explaining creativity in science, which is essentially about finding a reduced explanation of the phenomena around us, that follows a set of rules. However, I think Art is a much more complex space, especially after the 20th century, when the meta-game became about breaking its own rules.

We could dedicate an entire blog to exploring why art works: its ability to evoke emotions, encode meaning, and express concepts beyond mere beauty. But here, we’ll focus on a single, amusing counterexample.

Black Square by Kazimir Malevich is a famous painting that, as its name suggests, is a simple black square. Despite its apparent simplicity, its debut caused an uproar, as it started a radical departure from established artistic norms. However, the depth of conceptual “compression” in this piece is huge. It encodes debates about the rules of art, the essence of artistic expression, the nature of the universe, and even the self. Malevich considered the square the purest and most basic form of art, stripping away unnecessary elements to focus on emotions, philosophical ideas, and abstract concepts rather than literal depictions. By this definition, and assuming the observer is aware of some of its meanings, Black Square could arguably be one of the most beautiful paintings ever created, given how much information it compresses into its minimalist form.

Now, let’s explore the other extreme. Imagine a painting on a wall that is 50 cm wide but infinitely tall. This artwork is made up of completely random dots of color with no discernible pattern. The artist’s sole intent is to create a piece that cannot be compressed. One might argue that a subjective observer could still derive meaning, seeing it as a reflection on the nature of art, the universe, or the opposition of randomness to compression. But even if we assume that human cognition could extract infinite meaning from this painting (something computationally hard), encoding the artwork would require an infinite number of bits. According to Schmidhuber’s theory, which associates beauty with the amount of compressibility, this painting should not be beautiful.

Yet, as a subjective observer, and I’m certain many others would agree, this painting could be perceived as beautiful, precisely because it elegantly highlights the tension between randomness and compression, among other topics. Then, this example indicates that beauty and human emotion might not be strictly bounded to compressibility.

Art is complex. It started by painting animals in caves. Now, free from rigid rules or the obligation to mimic reality, has become an entity exceedingly difficult to describe computationally. It inherently turns any theoretical framework against itself, challenging attempts at definitive explanation.

As a computer scientist working on artificial creativity, such an elusive domain is both a nightmare and an infinite source of fun and joy. As Edward Frenkel encourages, I will keep working on my science, open to paradoxes, because they often lead to new knowledge.

Are AI Models Already Creative?

Figure 7: Dadaism problem generated by Stable Diffusion

Figure 8: The Fountain, Marcel Duchamp

Artificial Neural Networks excel at automatically representing and compressing data, effectively separating different patterns within it. While Schmidhuber’s theory suggests AI models might already be creative, there’s a crucial distinction to make: though they can effectively compress historical data, they lack two fundamental aspects of creativity, the ability to search for “interestingness” and the capacity to create artifacts that compress previously unseen and undetected regularities. What they actually do is compress existing data well, providing some generalization in lower dimensions based on the data’s inherent behavior. However, they cannot search for and output novel insights about their environment or knowledge base. They lack a transformative approach to creativity.

Let me give you an example that I think really illustrates this point. Take text-to-image models like Stable Diffusion. They can take a description and create a probable image, but they’re not able to handle questions as prompts and respond with truly novel, valuable images. In my experience, high-quality art and creativity rarely work like “I want to paint a dog, so I paint it.” Instead, they often start with a question or an open-ended artistic intention. Here’s one that was very trendy in its time: “Create a work of art whose purpose is to reject the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society and art.”

There are no predetermined rules for responding to this prompt. The real challenge lies in finding an effective way to portray (compress) this concept. As observed in Figure 7, when given this prompt, Stable Diffusion typically outputs an amalgamation of common visual elements associated with words like “capitalist,” “reason,” “logic,” or “reject.” In contrast, Marcel Duchamp responded to this artistic intention (created by himself) with Fountain. Not a trivial response, but an extraordinarily effective (and compressed) one. Current AI models aren’t designed to learn this kind of non-trivial, divergent reasoning. The question remains whether this limitation arises from the models’ properties, the nature of the problem itself (probably it’s not solvable through gradient descent), or simply that we’re not training models on the right kind of data.

Some work suggest that including information about artwork generation context could improve results by helping models learn to relate context and idea origination to images [11]. An interesting experiment would be to collect a dataset pairing original artistic ideas with their resulting artworks, without including explicit information about what’s in the artwork. Could an AI model learn these non-trivial transformations and functions? Could it generalize a function that takes a creative artistic problem and, without explicit guidance about what objects to portray, produce ingenious results (either as images or as text, imagining an LLM capable of designing a creative response and then crafting the prompt for its own text-to-image model)? While interesting, my intuition suggests this wouldn’t work, primarily due to the fundamental nature of creativity. We might get surprising and interesting results, but we’d still be applying gradient descent to a task that may not be suitable for it.

When it comes to LLMs, the challenges are similar, though I’m more optimistic about their future. Having been trained on so much human experience, they’re remarkably good at aligning with human interests. I could see them potentially directing the search for interestingness in other exploratory agents, something more sophisticated than what we explored in our combinatorial creativity paper, where we used LLM-learned probabilities to search over the space of unexplored artistic concept combinations.

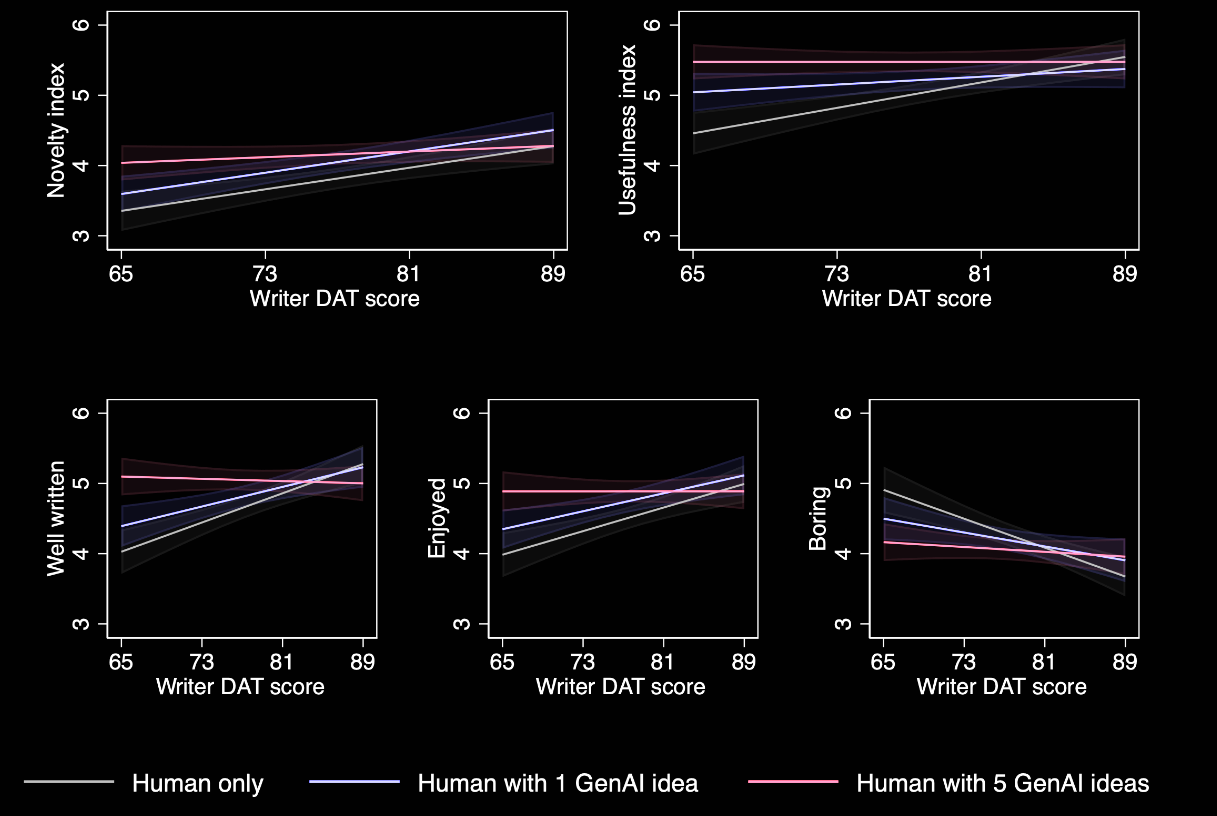

I often hear people claim that increasing an LLM’s temperature parameter makes it more creative, but I think this misunderstands both creativity and what temperature actually does. Raising the temperature just flattens the distribution of tokens in the output layer, increasing the variance of the results. But that’s not how creativity works, and research has shown it barely affects the novelty of outputs in creative tasks like story writing [13].

A more interesting study involves participants asked to write a story that will be evaluated by humans [14]. Some participants are allowed to use a large language model (LLM) to help, while others are not. Prior to the experiment, participants took a creativity test. The findings show that access to generative AI results in stories being rated as more creative, better written, and more enjoyable, particularly among less creative writers. However, AI-assisted stories are more similar to each other than human-written stories, and highly creative individuals saw little improvement when using LLMs. I would also have included the results of the creativity test for the evaluators. My intuition is that people who believe LLMs are highly creative might not be very creative themselves or may not be used to highly creative environments.

In short, if we define creativity as the ability to produce novel and valuable artifacts, AI models can be seen as creative by some set of subjective observers. However, their creativity is limited to specific, well-defined contexts (and to the subjective creative threshold of the observer). Unlike humans, who approach open-ended creative tasks through a divergent process, AI relies on convergent thinking. As we have seen, this heavily constrains their ability to create truly groundbreaking artifacts or discover entirely new regularities and knowledge, leading to outputs proper to transformational creativity. Divergent thinking is essential for innovation in environments without clear rules or objectives. In fact, studies suggest that AI can make human creative outputs more uniform, something that shouldn’t happen if they were divergent thinkers instead of convergent.

Regarding the Art domain, some artists, like Ted Chiang (the author of the beautiful Story of Your Life, which inspired the movie Arrival), argue that AI will never be an artist. Chiang claims that creating art involves making countless small, intentional decisions (every word chosen with purpose, every frame in a John Ford movie, every brushstroke in a painting). A system that generates probable outputs based on a brief prompt, he says, won’t truly understand or grasp the nuances of artistic creation. While I agree with Chiang that art involves constantly taking fine, crucial decisions, I believe this doesn’t rule out the potential for future AI systems. From the perspective of creativity as compression, each decision is made to resonate with the audience, conveying more than just the combination of words or brushtrokes. I believe we can design AI systems capable of divergent thinking, producing creative artifacts, whether artistic or not.

Figure 10: As DAT (measure of creativity) increases, the novelty and usefulness gains of using LLMs decreases

Open-endedness

Life is inherently open-ended. As humans evolved from mere survival to beings of higher reasoning, we became detached from our primal goals, leaving us without a clear, definitive purpose. Similarly, Art has an open-ended nature. It began as a way to leave a mark on the world and communicate a message but has transformed through cultural evolution into an ever-shifting and elusive domain. Once, we painted what we saw; then, we painted gods. When gods fell, we painted ourselves, and later, when there was anything left we started breaking the very rules we created. Currently, Art follows one guiding principle: to perpetually destroy itself, always questioning what it is, or isn’t.

The concept of open-endedness, pioneered by Kenneth Stanley among others (earlier Schmidhuber’s approaches, while not defined exactly in this way, are closely related to this concept), and further defined in [15], feels fundamental to me. It’s defined as the ability to continuously generate novel and learnable artifacts or behaviors that are unpredictable yet meaningful to an observer. This definition shares parallels with compression progress theory, particularly in how it values novelty and learnability. If something is too predictable, it’s boring (low learnability). But if it’s completely unpredictable, it becomes impossible to learn from, it’s also boring.

Take AlphaGo as an example of a simple open-ended system. Throughout its training, it developed policies that were genuinely novel to human experts, making moves that professional players would consider highly improbable, yet proved effective. Moreover, it has been shown that human players could actually improve their game by studying and learning from AlphaGo’s unexpected strategies.

Nevertheless, current AI systems, including foundation models, aren’t truly open-ended. They’re limited by their training data, unable to continuously generate genuinely novel insights. This is where the exciting gap lies, creating AI systems that can propose their own problems, explore without clear reward signals, and genuinely expand knowledge.

Looking ahead, I’m think that open-endedness is crucial for truly creative AI. While current open-ended systems may not be sufficient, they point us in the right direction. Attempting to build creative systems without open-endedness would severely limit their capability.

Imaging systems that can uncover discoveries that humans might find highly improbable or overlook due to cognitive limitations. Our computational abilities, our intrinsic knowledge shaped by evolution, and the patterns we learn from our environment, while invaluable for making remarkable discoveries, also come with limitations and biases that can occlude certain possibilities, constraining our ability to explore parts of the discovery space that could hold significant potential.

If we could rerun human evolution, would we arrive at the same scientific and cultural knowledge? I belive that AI has the potential to help us explore these overlooked spaces and facilitate groundbreaking discoveries that advance human knowledge.

One way to make this happen is by using reinforcement learning. The system would start by learning the core dynamics of its environment, understanding the key features, and figuring out how to take effective actions. After that, it could explore this space in a more open-ended way, coming up with fresh and valuable insights by tweaking these representations and checking the results for novelty and interest. Finally, the system could suggest new questions or challenges to tackle, driving both learning and creative problem-solving. This approach could be really helpful for solving problems in rule-based areas where the goal is to discover new knowledge, not just remix what’s already known.

On the other hand, feedback environments are essential in open-ended fields like science and art. Agents could engage in a feedback loop, creating artifacts that are evaluated by their peers, learning from the process. This approach could mimic the evolution of culture and knowledge, driving continuous exploration and innovation in creative disciplines. It could leverage the speed difference between artificial simulations and human evolution to explore alternative paths of cultural or general knowledge development. This process could lead to more “alien” knowledge discoveries, insights that are highly unlikely for humans to uncover due to cognitive biases like temporal, geographical, social, or computational constraints, as we discussed earlier. A notable example of such a discovery is AlphaTensor’s achievement in finding new matrix multiplication algorithms, discoveries that are improbable for humans due to the vast complexity of the solution space [16].

Art poses an even greater challenge. As we have previously seen, Art exemplifies what emerges of multiple open-ended systems interacting over an extended period of time and without a fixed goal in a shared environment. The artistic enviroment is not constrained to follow predictable empirical data but bounded only by what is computable within the human mind. Human art advances through a rich cultural evolution, influenced by diverse agents and external factors.

It would be fascinating to simulate something similar in AI: imagine multiple open-ended systems evaluating each other’s creative outputs and learning divergently through an evolutionary process. This could lead to the creation of Art in an entirely “alien” way, where the human is no longer the subjective observer. Such an experiment could give us a deeper understanding of creativity and a perspective of Art as a real external observer.

We stand at the intersection of human creativity and AI, we are witnessing an extraordinary moment of growth in this aspect. However, we need to be sure that we are optimizing in the correct direction, not a dead-end. While current AI systems may not fully replicate the divergent, open-ended thinking that characterizes human creative expression, we have not yet hit an unbreakable wall.

References

[1] Pelaprat, E., & Cole, M. (2011). “minding the gap”: Imagination, creativity and human cognition. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 45(4), 397–418.

[2] Hassabis, D., & Maguire, E. A. (2009). The construction system of the brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1263–1271.

[3] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperPerennial, New York, 39, 1–16.

[4] Thagard, P., & Stewart, T. C. (2011). The aha! experience: Creativity through emergent binding in neural networks. Cognitive science, 35(1), 1–33.

[5] Gero, J. S. (1996). Creativity, emergence and evolution in design. Knowledge-Based Systems, 9(7), 435–448.

[6] Boden, M. A. (1998). Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence, 103(1-2), 347–356.

[7] Boden, M. A. (2004). The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms. Routledge.

[8] Franceschelli, G., & Musolesi, M. (2023). On the creativity of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.00008.

[7] Feng Shi and James Evans. Surprising combinations of research contents and contexts are related

to impact and emerge with scientific outsiders from distant disciplines. Nature Communications,

14(1):1641, 2023

[8] Jamshid Sourati and James A Evans. Accelerating science with human-aware artificial intelligence. Nature human behaviour, 7(10):1682–1696, 2023

[9] Varshney, Lav R. “Limits Theorems for Creativity with Intentionality.” ICCC. 2020.]

[10] Schmidhuber, J. (2008, June). Driven by compression progress: A simple principle explains essential aspects of subjective beauty, novelty, surprise, interestingness, attention, curiosity, creativity, art, science, music, jokes. In Workshop on anticipatory behavior in adaptive learning systems (pp. 48-76). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

[11] Dreyfus, H. L. (1972). What computers can’t do: The limits of artificial intelligence.

[12] Wang, Haonan, et al. “Can AI be as creative as humans?.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01623 (2024).

[13] Peeperkorn, Max, et al. “Is temperature the creativity parameter of large language models?.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.00492 (2024).

[14] Doshi, A. R., & Hauser, O. P. (2024). Generative AI enhances individual creativity but reduces the collective diversity of novel content. Science Advances, 10(28), eadn5290.

[15] Hughes, Edward, et al. “Open-Endedness is Essential for Artificial Superhuman Intelligence.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04268 (2024).

[16] Fawzi, A., Balog, M., Huang, A., Hubert, T., Romera-Paredes, B., Barekatain, M., … & Kohli, P.(2022). Discovering faster matrix multiplication algorithms with reinforcement learning. Nature, 610(7930), 47-53.